Chapter 13

In Moscow for a week or two on my way home to England in the fall of 1929, I became aware of the shadows of terror which were already closing in on Russia. Nevertheless, back in London I threw myself into the work of the British Communist party, and tried to bury in my subconscious my doubts concerning the Soviet socialist new order. I worked for the British Communist party among the textile workers in Lancashire and campaigned for the Communist candidate at a by – election in Sheffield. I became a member of the Industrial Committee of the Party in London and wrote articles for Communist publications. I had won a reputation as an expert on costs of production in the cotton industry by my Manchester Guardian articles, and the endorsement of the results of my research by the International Master Cotton Spinners Association. Instead of cashing in on it by contributing well paid articles to the “capitalist press,” I wrote a pamphlet for the Communist Party on “What’s Wrong with the Cotton Trade.”

Arcadi sent me money and I took no payment from the Party. I was able to resume giving lecture courses for the Workers’ Educational Association, thanks to Barbara Wootton.(Later Lady Wootton and a member of the House of Lords.)

I was also busy on my first book Lancashire and the Far East, which I had begun writing in Japan. I read the works of Marx and Lenin conscientiously and thoroughly, and tried to explain in simple language the basic tenets of the Communist faith which, if one could make them clear to the workers, must make them see that only through the unity of the workers of the world could living standards be improved and unemployment eliminated.

In speaking to the Lancashire cotton operatives, I came up against the basic dilemma of the Marxist revolution, and also against the obstacle of the Comintern’s indifference to the sufferings of the working class.

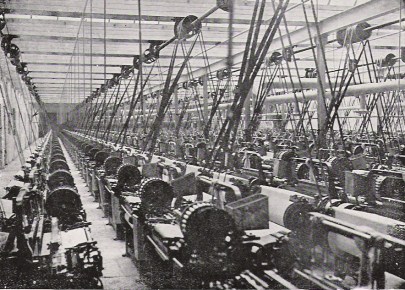

How could one convince the Lancashire cotton operatives that they should refuse to allow the cotton industry to be rationalized, refuse to work more looms, and go on strike for higher wages, when they knew as well as I did that the immediate result of such action would be more unemployment through the loss of more markets to Japan and other competing countries? To my mind it seemed clear that the basic need was to explain Marxist theory to them, to make them understand the meaning of “Workers of the world, unite” by showing that if all textile workers in all countries got together in one organization they could establish higher wages for all; to make them understand that the capitalist system based on production for profit inevitably doomed them to increasing poverty now that other countries besides England were industrialized, and workers in the East with lower standards of life competed against them.

In my pamphlet (What’s Wrong With the Cotton Trade: An explanation of the present depression and the Communist policy for cotton workers. Published in 1930 by the Communist Party of Great Britain) I endeavored to express in simple language the contradictions of the capitalist system” which forced one to the conclusion that socialism was the only way to solve the problem of poverty in the midst of plenty. “Is it true,” I asked, “that because more of everything is being produced all over the world, all workers must be made poorer by wage reductions? Is it true that because the total quantity of goods which the world can produce has grown greater, all workers are to have less of these goods?” This I continued, “is actually what the employers – the capitalists – argue and this is the position under capitalism . . . .” Because, I explained, giving the classical Marxist explanation, “under the capitalist system under which we live, the workers receive much less in wages than the value of the goods they produce.”

I possess a torn and battered copy of this old pamphlet of mine, thanks to my old friend and former comrade in the British Communist Party, Michael Ross, who, after abjuring Communism emigrated to America ahead of me and was foreign adviser to George Meany at the American Federation of Labor when he died in 1964. Reading it now, I consider that I did a pretty good job of setting forth in easily understandable terms the basic Marxist theses which were tenable at that time but which have, happily, been refuted during my lifetime by the transmutation of the “capitalist system,” in the advanced Western countries into something far better and more progressive than the sterile and stultifying “socialism” of the Communist powers.

By retaining the profit motive as its dynamo but accepting the necessity for some state regulation or control, the system we still call capitalist has demonstrated its capacity to produce more for more people than the socialist system which, in practice, has been found to require compulsion in order to function, and is consequently as inefficient as slave systems of bygone ages, although likewise formidable in war.

Back in the 20’s and 30’s, international socialism seemed the only way out, and even today one can question whether, had it not been for the Communist and National Socialist challenge and menace, the “capitalist system” would ever have resolved its contradictions.

It is I think wrong to regard the USSR and the USA today as having developed similar systems from opposite premises because this too optimistic world outlook disregards vital political factors. Despite the resemblance between the ever less socialist Soviet economic set up and the increasingly “socialist” capitalist system, the fundamental difference remains between government by consent of the governed under the rule of law, and that of an autocracy- or communist oligarchy relying on complusion to preserve its privileges and powers. Nevertheless there is truth in the Hegelian theory of thesis, anti-thesis and eventual synthesis, as applied to the development of the free enterprise and opposing socialist systems of our time.

One can also view the course of human events in my lifetime as illustrating basic truths expressed in the Morality Plays and legends of the “Ages of Faith.” Fear of the devil and hell, caused many a king, baron, or knight and others enjoying temporal power, to behave somewhat better to their subjects than they otherwise would have done, just as in our times the fear of Communism leads to reform.

In England in 1930 I found myself up against the Comintern, which was then pursuing an ultra-left policy and insisting that agitation, agitation above all, was the function of Communist parties.  No theoretical explanations, no waste of time or energy in exposing the dynamics of capitalism; just tell the workers to strike and strike whatever the consequences. The Comintern, already transformed into an arm of the Soviet government, was not concerned with the livelihood of the workers; it aimed only to weaken the capitalist states by continual strikes and the dislocation of economic life. Its primary objective was the safety of the USSR and it cared nothing of the interests or sufferings of the “toiling masses.”

No theoretical explanations, no waste of time or energy in exposing the dynamics of capitalism; just tell the workers to strike and strike whatever the consequences. The Comintern, already transformed into an arm of the Soviet government, was not concerned with the livelihood of the workers; it aimed only to weaken the capitalist states by continual strikes and the dislocation of economic life. Its primary objective was the safety of the USSR and it cared nothing of the interests or sufferings of the “toiling masses.”

One day in Blackburn, the great weaving center of Lancashire, an elderly textile worker complained bitterly to me that it was all very well for the paid officials of the Communist Party to get themselves arrested for deliberately and unnecessarily holding meetings where they obstructed the traffic, but how could we expect workers with families to do so, since it was an utterly useless performance? He did not know how proud Communist Party members were if, when they went to Moscow, they could boast that they had gone to jail in the class struggle. Such an accomplishment might be held to wipe out the stigma of their non-proletarian origin.

(In Moscow some years later I was to meet again an unemployed worker and his wife with whom I had stayed in Sheffield while speaking for the party. Appalled by the miserable condition of the Russian “proletariat” he went home to affirm that living on “the dole” was preferable to being employed in the “Workers’ Paradise.” Which reminds me of a joke current in Russia in the hungry thirties. Two elderly women formerly good friends meeting by chance on a Moscow street ask each other how they are faring. One is very poor and hungry, the other tolerably well off. “Is it your son Boris who helps you, or Ivan?” the hungry one asks. “Oh no,” replies the other, “Boris is an accountant who can barely provide for his own family and Ivan who works in a factory is even worse off. It’s Dimitry who helps me.” “Dimitry? What does he do?” “He emigrated and is unemployed in America.”

This “joke” was based on the fact that in those days two or three dollars a month in valuta enabled one to buy at Torgsin at cheap world prices the butter and eggs and meat unavailable on ration cards.

I can remember once finding two English pennies in the pocket of an old suit and journeying by streetcar with Jane to buy one egg at Torgsin with which she baked a cake.)

Finally I got myself into trouble with the Politbureau of the Party in London on account of an article I wrote which my friend Murphy, editor of the Communist Review, had allowed to be published. I had been reading Lenin’s writings of the “Iskra period” and had discovered that he condemned the “Economists” who maintained that the intellectual has no role to play in the Party and that the socialist idea can spring “spontaneously” out of the experiences of the working class. Lenin had insisted that the ordinary worker, by the experience of his daily life, develops not a full revolutionary class consciousness but only that of a trade-unionist. Clearly, to my mind, in this period of declining markets for Britain, the workers’ trade-union consciousness was likely to impel them to accept wage reductions and join with the bosses in attempting to recapture their markets. I did not foresee that this would lead Europe to a fascist development, but I perceived that, unless the Marxist conception of international working-class solidarity could be put across to the workers, they would perforce unite with their employers against other countries.

Already, during the First World War patriotism had proved more potent than Social Democracy. Soon it was to be demonstrated that Hitler and Mussolini could rouse their people to gird for battle under the slogan of the “proletarian nations” against the “Pluto-democracies.” Similarly today the “underdeveloped” countries of Africa and Asia show a tendency to unite against the industrialized West – “Have Nots” against “Haves” in the international arena instead of at home.

Although my article was buttressed by quotations from Lenin, I was held to have deviated seriously from the Party Line by maintaining that theory was of primary importance and that the intellectual should not play at being a proletarian, since he had an important part to perform in enlightening the workers and convincing them that socialism was the only solution for unemployment and poverty in the midst of plenty. I was not directly accused of Trotskyism, but I was held to be slightly tainted with heresy.

Even at this stage of my Communist experience I had not the sense to see that nothing good would come out of the USSR and that the foreign Communist parties were already corrupted and impotent. I had a great respect and liking for Harry Pollitt, Secretary of the British Communist Party, who had been my friend before I joined the Party and now prevented the little bureaucrats in the Agitprop Department from sabotaging my pamphlet and my Party work. To this day I find it difficult to understand how this British working-class leader of Nonconformist Christian background came to subordinate his conscience and sacrifice his personal integrity to become a stooge of the Stalinists. In 1930 the fact that Harry Pollitt who was a principled, kind and intelligent man of integrity and courage led the British Communist Party deluded me into thinking that it was still a genuine socialist working class party. Six years later in Moscow I was to be shocked at Pollitt’s failure to make any overt protest when Rose Cohen, his much loved mistress was arrested and condemned to a Soviet forced labor camp. True, she had since then become the wife of Petrovsky alias Breguer, the big shot in the underground Comintern apparatus about whom I have already written. Nevertheless one might have expected Pollitt to make an effort to save her.

My basically liberal aspirations and my false conception of the nature and aims of Communism four decades ago, have relevance today, because so many of those who now control the destiny of the newly independent states of Asia and Africa harbor the same illusions about socialism as I had in the 20’s.

Listening to Nehru in the 50’s was like an echo of my own youth when I knew and understood as little about Communism as he did until the end of his life. And still today although other leaders of the “Third World” have learned through experience bitter truths about the real aims, methods and practices of the Communists, they still conceive of “socialism” as synonymous with social justice.

When I asked my Indian friends what hold the diabolical Krishna Menon, whom I had known in London as a Communist, had on Nehru, I was told “Just Nehru’s belief in Socialism.” And as late as 1961, Cheddi Jagan, Prime Minister of British Guiana, the then latest British colony to become an independent state, visiting Washington hoping to obtain money from “capitalist” America, told the National Press Club that “only state control of production and distribution can pull a country up from poverty.” Nor did such statements apparently lessen his chances of a loan from the U.S. As why should they. since Nehru, whose disapproval of the West was matched by his soft attitude toward Soviet Russia and Communist China, had been given so many millions or was it billions? Harold Laski both during his anti- and pro-communist phases was the most widely known of the professors at the London School of Economics who exerted their influence in the socialist direction. They can be held largely responsible for the political illusions of the elite of Asia and Africa, educated in British schools and universities, who now control the destinies of most of the newly independent countries of the former “colonial” world. Harold Laski is dead and the good he and his disciples did in awakening the social conscience of the Western world to the abuses of the “capitalist imperialist” economic and social system of the past is interred with their bones. But the evil they did lives after them in the influence still exerted by their teachings in the “Third World” and among old American New Dealers.

In spite of the abundant evidence provided by the USSR and the “People’s Republic” of China that “socialism,” far from offering an escape from poverty and injustice, rivets on those who succumb to its lure a tyranny from which there is no escape, the Asian and African students who were my contemporaries at the London School of Economics in the 20’s, and those who came after me seem to have learned nothing and forgotten nothing since their student days. They still see the “capitalist imperialist” world as it was then while viewing the Communist empires through a mist of illusion. They continue to believe that “socialism” is the way to emancipate their peoples from poverty, and ignore the terrible lesson taught mankind by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and, more recently, by Communist China.

While the West has developed a new economic and social system which combines the dynamics of a competitive ‘capitalist’ economy with the major benefits of a “welfare state”, the East, in particular India, became worse off under the doctrinaire Socialist Nehru than under the British.

The old proud and unrepentant British Imperial rule over subject peoples in Asia and Africa is gone with the wind. But British socialist influence over the generation of Asian and African intellectuals who now rule their emancipated countries still impregnates their political conceptions like a delayed-action fallout.

In April 1960, in Baghdad I remarked to the British Ambassador, that England had to a considerable extent been successful in substituting London School of Economics graduates, and others nurtured in the Socialist philosophy in English schools and colleges, as the new ruling class in Asia, in place of the princes and “feudalists” who had been Britain’s collaborators in the past. Sir Hugh Trevelyan, who is one of Britain’s cleverest and best informed ambassadors, responded with an appreciative laugh. Nor did he dispute my surmise that the course of events in Iraq had shown that “tame” socialists nurtured in the Fabian Socialist philosophy, were all too prone to kick over the traces and become Communists or communist collaborators in times of stress. It is of little or no importance to Moscow whether or not their collaborators have aims different from theirs so long as they continue to damn America for being capitalist and imperialist while never condemning Soviet Russia because of its socialist halo.

No doubt it was useful to the British that they had a second string to their bow in Asia and Africa in the persons of the Fabian Socialists they had nurtured in their schools. The British “ruling classes” have continued to demonstrate their cleverness in staying on top whatever economic, political and social system prevails. In ages past younger sons of feudal lords joined the ranks of the rising mercantile class. Today, after education in the best schools and universities, the sons of the privileged become Labor Ministers advocating “Progressive policies.”

While I had been in Japan enjoying the best year of my life, Temple was going through a very bad period of his.

Endeavoring to perform the arduous duties of House Physician at the Metropolitan Hospital in spite of having one lung deflated by a pneumo-thorax operation, he had temporarily lost his usual zest for life, was drinking too much, and seemed not to care if he killed himself.

Temple used to say that one regrets most not the things one has done which might better not have been done, but those one failed to do. So I am happy now to have found a letter I wrote him from Tokyo which, in contrast to my many complaints over the years that he failed to contribute his fair share towards Mother’s support, expresses my love and concern and appreciation of my brother. Writing to him from Tokyo in February 1929 I said:

“Since I got Mother’s last letter I have been thinking a lot about you and discovering that I love you very much. Although I have seen comparatively little of you these last years you fill a big place in my life and Mother’s letter has upset me. You must do your best to live, Temple. You have always found life good. Is it no longer so? Give up this hospital job and get one on a ship or in a sanitarium. It is worth caring for yourself, Temple, even if you will never be very strong. You have always found so much in life intellectually and surely this must be more than ever true now? Only a short time ago I wrote to Mother that after all it would be you who did the big things….

You remember how Arcadi said you could never be “decomposed.” He meant, I think, that for you, the intellectual, objective interests would never be lost. Arcadi liked you so much, Temple. And I find in him all the things I remember of Dada, plus a lover. I am a little afraid of my happiness-the gods are sure to be jealous. I suppose I idealize, but that does not matter. For me he is the perfect lover, comrade, playmate, and husband. We both want a child but are both afraid of what it may do to me-Arcadi wants me to be the old Freda. It is difficult to try to be the two incompatible things in women. To be a woman and yet to work like a man, to look at life like a man does.

I wish I had you here to talk to, Temple. I understand so many things I never understood before. Take care of yourself Temple-life is good. Even for you, Temple, with one lung. Do be sensible about your work and give up this job.

Write to me if you ever have time and tell me what is wrong. I really do love you very much and I know how much I have learnt from you, some of it unconsciously.”

By the time I returned to England Temple had secured an appointment on the staff of Colney Hatch,  the famous and largest mental hospital in England. Now as I prepared to leave for Moscow, Temple was about to fulfill his long cherished dream of voyaging to the South Seas.

the famous and largest mental hospital in England. Now as I prepared to leave for Moscow, Temple was about to fulfill his long cherished dream of voyaging to the South Seas.

In recalling nearly 40 years later my last year in England as an active member of the Communist Party, I remember best the last days I spent with my brother sailing along the coast of Devon and Cornwall before he took off on his long voyage to find his “dream islands” in the South Seas.